13 Senior Year

Today I would be considered a nerdy boy, socially-awkward.

Although I certainly wouldn’t have won any awards for “most social”, I think it would be hard to peg me as shy or reserved during my final year in Neillsville.

I had friends. I was active in school activities. Nobody would have voted me “most popular”, but in a class of fewer than 100 kids, I knew everyone, and everyone knew me.

13.1 College Applications

During the fall, I was busy preparing my college applications. Today’s kids use terms like “safety school” or “reach”, and they confer with guidance counselors and college consultants to pick the right combination of prestige, selectiveness, geography, and personal fit.

Among my high school and church friends, college seemed very optional. Only a few of our parents had attended college. My father, like our school teachers of course, had a bachelor’s degree. But among the farmers and small businessmen who made up our community, college was at best an optional luxury and for many it seemed like a waste of time. Unless you’re planning to become a doctor, or some professional that requires the degree, what’s the point?

This general attitude meant that there was little or no pressure to apply to colleges. Everyone was supportive to any student who wanted to go to college, but our parents and community were supportive of other choices too. Trade school was a common option: a year or two of study could qualify you as a plumber, an electrician, a welder, a secretary – perfectly acceptable ways to earn a living. If you had a family or relative already in one of those businesses, you could skip the school completely and simply learn on the job.

But I wanted to go to college (Chapter 27). I liked school, I was good at it, and thought nothing would be more fun than to learn more in-depth about so many of the exciting ideas, especially about the computers and technology that I was already learning on my own. I can’t underestimate how important it was that, meanwhile, my close penpal relationship with John Svetlik was shaping my choices. When John told me about how he’d like to attend one of the major schools, like Stanford, I took him seriously. I wrote to the colleges myself to ask about the application process. I borrowed books from our guidance school library that explained the SAT testing process. Books that included rankings appealed to my competitive spirit, and it was natural for me to ask why not go for the best.

I applied to exactly three schools:

- Stanford University

- MIT

- University of Wisconsin - Madison

Each application was completely different from the other. Long before the introduction of today’s “Common App” and other standardized processes, the written applications required different letters of recommendation and different essays. Except for my MIT essay, which I wrote on a typewriter, all of my applications were handwritten in ink.

Madison was my “safety”. As an in-state resident with good grades, my admission was all but guaranteed and I didn’t even consider the possibility that it might not happen. If anything, I assumed this was the most likely scenario, and I even had friends who discussed informally the possibility of possibly living together while there. My father had attended for a year, and of course we had visited the city a few times so it felt very doable and real.

Looking back, I’m not sure I understand how I came to apply to the other schools. Our high school library had one of those books that ranked colleges by their selectivity, including test scores. I didn’t have SAT results when I began the application process, but I assumed I was well within their acceptance range. I knew from my competition with John Svetlik that I wasn’t the top of the top, but there’s always a chance, right?

So I wrote letters to Stanford, and then MIT, asking them to mail me the application materials. I absorbed every page they sent me. Even today I remember the sepia colors of that Stanford booklet, with its pictures of palm trees and happy-looking students. The MIT catalog, with its focus on technology and hard-core science: I loved it even if, unlike Stanford, it was accompanied by wintry photos of a campus covered in snow.

MIT required an in-person interview, an hour’s drive to the bigger city of Wausau. My long-suffering parents took me there at the appointed time and I met an elderly man who engaged me in an informal chat in which I think I did reasonably well. But he ended the interview with a nonchalant question about which other schools I was targeting and which was my top choice. “Stanford,” I replied innocently.

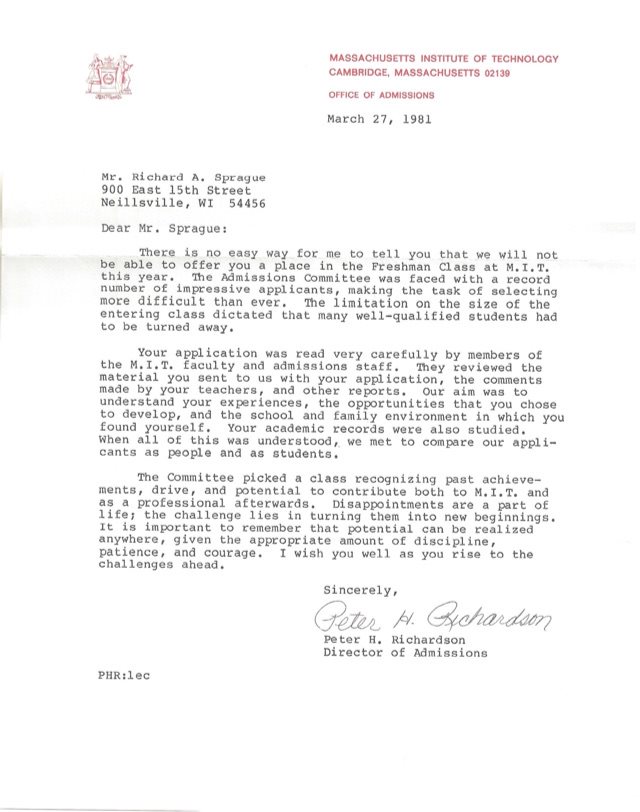

So perhaps it was no surprise that in March I received my first rejection letter.

The letter arrived on a particularly dark day, along with news of the assassination attempt on President Reagan. The hopes and dreams I had established for myself seemed to be colliding with reality.

Exactly one week later, mother picked me up from school and on the ride home she mentioned that I had received a letter from Stanford. I had already braced myself for the inevitable rejection, but then she added another detail that hadn’t occurred to me: “It’s a very thick envelope,” she said.

13.2 Graduation

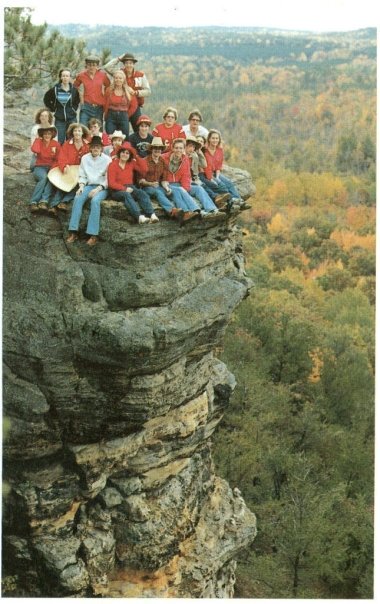

By the end of my senior year, I finally felt adapted to the Neillsville social environment. In a small school, everyone knew me, but through my accomplishments and my involvement in their lives, I discovered that I had more personal relationships than previously I had thought.

I had never been particularly stressed about grades. I could get A’s just by paying attention in class. People, including teachers, thought of me as the class brain, so on the one hand I guess I had something to prove, but on the other hand, I was often left alone. The bottom line is that Neillsville wasn’t an especially challenging place academically, so there was little or no pressure to go above and beyond the minimal requirements. I didn’t pay too much attention at the time, but I suppose probably the bottom half of the class was pretty poor academically, so it may not have been all that hard to shine in a place where the bar wasn’t particularly high.

You’d think that in that environment, achieving valedictorian status would be a slam dunk, but no: that honor went to Gina. The number two salutatorian spot went to another girl, whose name I barely remember. The GPA calculations that determined class rank included the grades from physical education classes, in which I had never scored an A, and more often than not was a B. My final GPA was something like 3.85.

Anyway, by graduation time I had already been accepted to my dream school and these honors no longer meant anything to me. Probably I was also plagued by a touch of arrogance, a lifelong affliction that caused me to feel and act like I was better than these kids and therefore didn’t really care which awards they won.

That said, I would have enjoyed giving a speech at graduation, but alas the honor fell to others. Gina was a quiet, somewhat soft-spoken girl, the daughter of our home economics teacher. Non-intuitively for somebody who had never been involved in sports, she chose as her valedictory speech a theme about football, something about competing to win, or advance the goal, or – I really don’t remember. The number two person also got to say a few words, and the rest of us, the top ten, were invited to sit on the main stage looking on behind them. I sat next to Jimbo, who chuckled when I held up a “Hi Mom” sign to the audience in front of us.