17 Family

17.1 Grandparents

I was lucky to know my grandparents and great-grandparents well.

My mother’s parents, the Pulokases, lived a half-hour’s drive north, on a small farm in Reseburg Township near Thorp, Wisconsin. My father’s lived about an hour away, just outside the tiny community of Sheldon, Wisconsin. Both sides of the family were active dairy farmers until I was a teenager, so cows, tractors, and hay fields were a natural part of our lives.

17.2 Pulokas Grandparents

The Pulokas relatives of my mother’s side were among the 350,000 immigrants who left Lithuania in the last half of the 19th century. Descended from a man named Matthew Pulokas who arrived in Franklin Vermont in 1900, settling in the Chicago area along with his brother Carl.

Matthew moved to America as the result of what appears to have been an arranged marriage, to Domecella Winskunas a year after his arrival. Like most immigrant farming families, they had many children—ten or more—but only three survived to adulthood, all boys, including my grandfather Anton. The family worked a small diary farm, purchased in 1904, on the south fork of the Eau Claire River in northern Clark County.

The farm was small, and by the time the brothers were in their teens it was no longer necessary to have the entire family work the place, so Anton instead found work as a truck driver, hauling cargo from northern Wisconsin to Chicago every day for a dozen years, until he was able to buy a farm of his own. His property, conveniently located adjacent to the rest of the family, became the home of my grandmother, Martha, the birthplace of my mother and her younger brother, and a wonderful place to play for me and my siblings.

Meanwhile, Carl had a daughter who married a Shainauskas man who died in the 1940s, widowing his Pulokas wife who raised her son Frank in the Chicago area. Frank was much younger than his two older sisters, who both joined a Lithuanian Catholic convent in Chicago. Frank visited the Pulokas farm during his childhood summers and the family remained in contact for the rest of their lives.

My mother’s two uncles, Walter (1902) and Joe (1904) never married but remained at their birthplace, working the farm for their mother while she was alive, and continuing to run the place, hunting and fishing until they themselves were too old to work anymore. Lifelong bachelors, they apparently had no interest in the basics of housecleaning after their mother died. The inside of the house was a mess, with a 1936 calendar posted above the kitchen table, untouched over the years that I visited.

I remember occasional visits to their home as we listened to them talk about the weather. The brothers had uncanny memories about anything weather-related. We could pick a random day anytime in the past half-century and the two would instantly tell us what the weather had been like that day or week.

You could pick any specific date, like “February 2nd, 1944”. Joe would answer “That was cold”. “Ten below”, his brother Walter would add. “A couple days before that big snow storm”, Joe might clarify. They could offer similarly detailed recollections about weather for any week, any decade.

The three brothers left school after the third grade to work full time on the farm, a common – and expected – fate for farm boys of their day. But if their educations were incomplete, it certainly didn’t show in their daily lives.

On our visits to his farm, Grandpa Pulokas would often sit in his rocking chair, head buried in a newspaper. He kept careful records of which cows he raised, how much profit per cow, and many other calculations that today we’d assume require a high school education. I still wonder how, statistically, it can be true that in America so many people graduate without the ability to read and write, when my country grandfather seemed to have no trouble, though he was only in a classroom for a few years.

From Ancestry.com:

When Mathilda Martha G Petruzates was born on April 26, 1905, on the Petruzates farm in Eagle River, Wisconsin. Family legend says that her uncle was charged with the task of registering her name with the town but was drunk and gave the wrong name. For that reason, she always went by her middle name, Martha. Her father, Anton, was 43, and her mother, Anna, was 34. Martha was 35 when she married Anton J Pulokas on May 1, 1940, in Thorp, Wisconsin. They had three children during their marriage. She died on December 17, 1979, in Neillsville, Wisconsin, at the age of 74.

How Martha ended up in Thorp, uprooted from her roots in Eagle River Wisconsin, is a story long lost to history. Well into her late 20s and maybe even past 30, supposedly she had come to the Thorp area to meet my great-uncle, Joe – Anton’s older brother. Nobody knows what happened that might have precipitated the switch.

The Pulokas farm was much smaller than the farms of my father’s side of the family, but to us that made it more personal and friendly. It may have been just that my grandmother Martha was an incredibly sweet and loving woman who greeted us with presents on each visit: her back room was always set up with new toys and was our first destination each time we came over, which was at least once a month.

My mother and grandmother were emotionally close as well, speaking on the phone nearly every day – in spite of the fact that in those days such long-distance calls were charged by the minute. The trip to Grandma’s farm seemed long to us – perhaps the lack of traffic in Neillsville made any trip seem far – through the rolling hills, across the many streams, and past the endless cornfields and pastures of central Wisconsin. Surrounded as we were by so much nature, I guess we didn’t appreciate the countryside as much as I do now and I regret not taking it more seriously and treating it more like the precious experience that it was.

There was never a shortage of things to do at Grandma’s farm. During the summers, with the good weather, we played non-stop outdoors, mostly in the front lawn but sometimes in the cow pastures extending to the woods. The only area we were afraid to venture toward was the back yard, where Grandpa kept a large and scary-looking bull, chained through his nose to a heavy concrete block. We imagined that the bull was dangerous, and we especially avoided venturing near it while wearing red colors, but I never saw it to more than lazily munch the grass and hay that Grandpa had set out for it.

Of course there were plenty of farm chores to do as well, and Grandma let us help: fetching eggs from the chicken coop, pumping water for the bulk tank to cool the milk, harvesting radishes and onions from her vegetable garden.

There were pets too. Grandma kept a house dog, a small mutt she named Buttons. Well-fed from her kitchen scraps, Buttons was the fattest, most obese dog I’ve ever known. He died at some point in my childhood, soon replaced by another half-breed, a chihuahua-like puppy she named “Pepsi”.

Although there were no house cats, like all dairy farms they had plenty of barnyard cats, fed on leftover cow milk and whatever mice or rats that attempted to live on the grain kept over the winter. The cats had many kittens, including one litter of three that Grandma gifted to each of us children. The kittens were to be kept at Grandma’s house, which provided yet another excuse for us to enjoy our visits there. Sadly, like many barnyard cats, these didn’t make it to adulthood, dying one by one of distemper.

Grandma had a green thumb, and her house and yard bulged with pots bearing all manner of flowers and greens. My mother would sometimes consult with her about various planting problems, and somehow anything Grandma touched would end up growing again.

Partly because Grandma was so enthusiastically interested in us, and partly because Grandpa was less loquacious, I didn’t interact much with my grandfather. I suppose he would have been busy with farm chores, less able to spend time with us, and maybe my brother and I would have had more interaction if we had been older and more useful on the farm. Still, I know Grandpa cared about us in his own way.

One birthday he announced that he was taking me to a store to buy me a football. Despite not being much of a sports-minded person, I accepted his gift gratefully, not wanting to explain that I’d probably not get much use out of it.

17.3 Death of Grandma Pulokas

In late Fall of my junior year in high school, my grandmother Pulokas came down with what seemed at first to be a sore throat. By the time we saw her at Thanksgiving, it was bad enough that her voice was scratchy, an odd symptom that continued through Christmas until, finally, sometime in the new year she visited a doctor.

I know little about the medical details – my teenage self wasn’t tuned to such things – but eventually we learned that the “sore throat” was a manifestation of lung cancer.

She was in and out of the hospital that year for various tests, and although I’m sure the adults were very concerned, none of the seriousness trickled down to me. She was just Grandma. Always Grandma. Always there.

Something happened that resulted in her admission to the big hospital in Marshfield, and I remember visiting her down the same long corridors that had been familiar to me during my own bouts of illness there: the ever-present statues and crucifixes that adorned St. Joseph’s Catholic hospital, no doubt of some assurance to lifelong believers like her.

Somehow I was left alone in the room with her when suddenly she blurted to me: “Well, just know that I’m ready.”

To my evangelical mind trained that salvation only comes through direct faith in Jesus, I found this oddly reassuring and concerning at the same time. I knew on the one hand that she was a serious, practicing Catholic; but on the other hand my Evangelical upbringing taught me to be suspicious of anyone who might hope to go to heaven based on anything but faith and grace alone. Catholics pray to Mary, not God, and think you get to heaven by listening to the Pope, right? Now I can chuckle at my ignorance, but Grandma’s earnest faith made an impression on me.

17.4 Sprague Grandparents

The other side of the family – the Spragues – seemed less approachable, a bit more stand-offish than the loving embraces we received from Grandma Pulokas. Part of the reason may have been geographical: The Pulokas farm was much closer, just over a thirty minute drive. My mother brought us there several times a month, even more when there was no school. But I can’t help thinking that some of the reason we saw the Sprague side as less friendly was that it simply wasn’t possible to be a nicer, kinder, woman than my Grandmother Martha Pulokas.

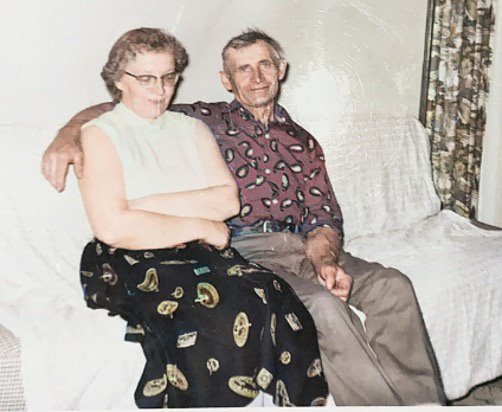

My grandmother Ruth Sprague was a faithful matriarch who broke every mold of the typical Wisconsin farmer’s wife. Besides the normal work of milking cows each morning, for decades she held a full-time job as a bookkeeper downtown at the farmer’s co-op, long before it was “normal” for a woman to have a job.

As the only one of her siblings who graduated from high school, she was proud of her literary tastes. The bookcase in her living room was packed with National Geographic, Readers Digest and various bound books of literature. I remember that she had a copy of The Koran up there someplace, which was exceptionally odd for a farm house back in those days, but that’s the type of person she was. She subscribed to the Wall Street Journal, delivered by mail a couple of days late to their rural farmhouse, but another hint at her curiosity about the world.

Her husband, my grandfather Donald Eugene Sprague, Sr., had no interest in reading as far as I could tell. Unlike my other grandparents, Grandpa Anton Pulokas, who always seemed to be reading a newspaper when we visited, I’m not even sure I could prove that Grandpa Sprague was literate. Well, that’s not completely true: to run a farm all those years I’m sure he was reasonably good at writing and math, but I don’t think he had his wife’s curiosity about the world.

Their farm was much bigger than the Pulokas farm, with many more cows, and hired hands whose names seemed to change regularly enough that we didn’t bother to get to know many of them. I remember Ted, who Gary and I found to be hilariously funny during our dinners together; and the Menchaka brothers, with their mysterious past – part Indian? Part something? Abandoned by their father?

In a farm community where most families were large, the Spragues were odd in that my father was an only child. Perhaps for that reason, after he left home my grandparents became foster parents, often for kids from troubled homes. I suppose the authorities thought that some time on the farm might teach discipline and skills they wouldn’t have otherwise learned.

One of these foster kids was a teenaged boy named Robbie who loved to play rough with my brother and me, wrestling us on the ground much more seriously than seemed appropriate.

We later learned that he had been placed in foster care at a very young age, after accidentally murdering another kid with a baseball bat. Robbie had a thing with baseballs: he broke one of Grandma’s windows with one. She demanded that he pay for the replacement out of his allowance money, but discovering that the cost would be higher than his allowance could pay, she promptly gave him a raise. This was how she thought about life.

Don (Sr) (my grandmother always called him “Don”) developed health problems as he aged into his 50s and 60s, probably due to his life-long cigarette habit. A relatively short man (maybe 5’8” or so), he had a slim build that gradually diverged as his wife became heavier. Sometime in the 1970s, he was diagnosed with kidney disease and had to go on dialysis.

They retired from farming to a life of regular long-distance travel, always by car, and generally to the west and south. My grandfather’s need for regular dialysis made no difference to their plans. Grandma simply looked up dialysis centers along the route, making regular stops as necessary.

Both of my Sprague Grandparents, like my father, had Type O-positive blood.

17.5 My Great-Grandparents

My grandparents were the last Sprague holdouts in an area that had once apparently been home to many of their relatives. Howard Sprague (1889-1975), my great-grandfather, had settled there in the 1920s or 30s and raised seven children, all of whom had their own farms at one point or another. After Howard left, the others left too, one by one, moving to cities out west in California or to the south, where they took part in the great American migration away from the farms, building lives in the cities that were much different from the agriculture-oriented world they left behind.

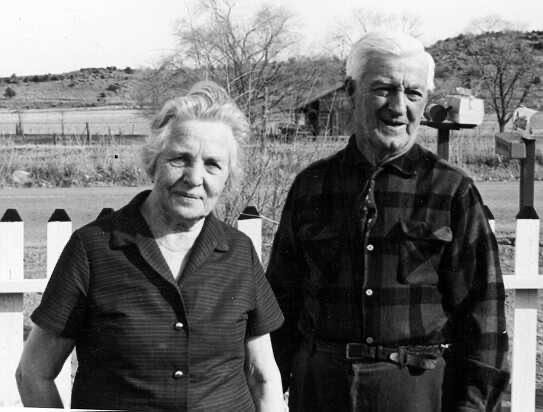

My great-grandfather Howard Sprague and his wife Delia were quite old, well into their 80s, by the time I met them, but they were both spry and full of energy, eager to meet us and spend time together. I feel very lucky that I had those several days to get to know them.

Howard Sprague was a perpetual optimist who enjoyed a life full of regular attempts at reinventing himself. Born in North Dakota, he lived as a farmer for many years while raising his family, ultimately settling in Sheldon, where my grandfather grew up and raised my father. Unlike many of his farmer peers, Howard seemed to do farming out of an interest in business: he saw it as a simple way to earn a living, buy seed for cheap, grow it until harvest and sell at a profit. But there were other ways to earn a living too, including home construction, which he did as a side occupation until, long before I was born, he decided to move near Monterrey California to start a commercial building business. He tried that for a few years, apparently successfully, before moving again, until he ultimately retired to Grand Junction, Colorado, where he lived until his death.

But back in Sheldon, somehow my grandparents held on, lone holdouts against the urbanization that called the rest of the family. As a result they gradually accumulated additional farms, left to them by departing relatives. This, too, made Grandma Sprague’s place seem so much bigger, and a bit more formal, since now the various additional farms were inhabited not by relatives but by renters.

Still, a farm is a farm and there is always plenty to do. Grandma Sprague had planted apple trees in her front yard decades before, and now during the late summer and fall the trees bulged with fruit begging to be picked. She too had a vegetable garden – far larger than the Pulokas one – with rows and rows of pumpkins, squash, sweet corn and much more. Of course, both grandparents’ farms were surrounded by thickets of corn plants, fields that by late summer grew into unnavigable mazes that we kids never grew tired of exploring. The Sprague farm had a separate, large hay barn, full of straw bundles that we turned into non-stop amusement, building our own caves and hideaways, like full-size lego bricks.

And always, the smell of cows, everywhere. “Fresh air”, my mother called it.