1 Neillsville

Rural America underwent its biggest changes in the first half of the twentieth century, long before I was born. From an economy that was 90% agriculture to our modern, urban one, what used to be considered the backbone of American culture has gradually faded into history.

Not for me.

1.1 A brief history

During the 1960s and 1970s, small farm-centered towns like Neillsville were already becoming marginalized in American culture, but the older residents – my teachers, civic leaders, and relatives – remained in a world that would have been recognizable a half-century before me.

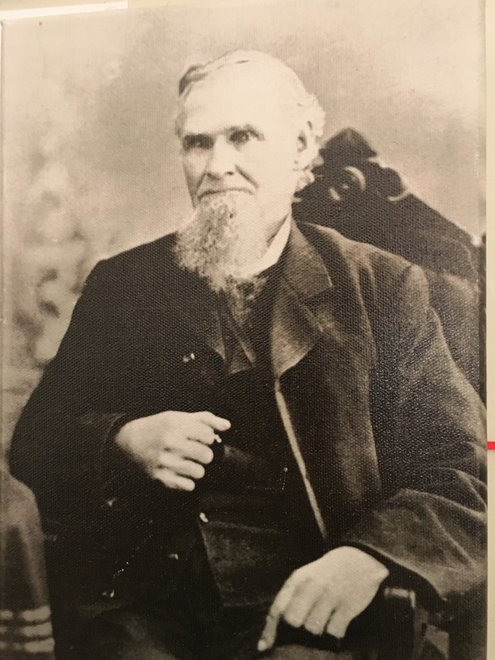

By the time I was born in 1963, Neillsville’s main industry had long since switched to dairy farming, but that was a modern development. Settled originally in the 1840s, it was the plentiful forests and the promise of a lumber business that first brought James O’Neill here, building a sawmill on the creek that bears his name. By 1854 the community that had developed around it was important enough to be chosen as the county seat.

Lumber was an important business through the 1800s. The nearby Black River was in those days wide enough for commercial navigation, flowing through the heart of central Wisconsin all the way to the Mississippi River. As O’Neill’s Mill processed the plentiful oaks, chestnuts, elms, and birch of the forests into lumber, land was cleared for farming corn, oats, and soybeans, and hay for grazing animals, especially cows.

By the early twentieth century, much of Central Wisconsin was becoming a center for milk production, for cheese and butter-making, now exportable to the cities via the railways that crossed the state. Rolling hills and forests, punctuated by plentiful water from small streams and lakes made it ideal for dairy farming. The geography as well as the climate was familiar to north European immigrants from Germany and Scandinavia, who came in droves, attracted to the excellent farmland and not intimidated by the cold, long winters. These hearty settlers and their big families soon multiplied and integrated, so that by the time I arrived, the only memory of Europe was in the names: Shultz, Larsen, Elmhorst, Opelt, Makie, Mengle, Swensen, and dozens more names that were so common I assumed the whole United States was populated this way.

Most of these immigrants came originally by train, from the teeming drop-off places in Chicago. My grandparents spoke routinely of the importance of the trains in their childhoods, but the Neillsville train station had been long abandoned for passenger service by the time I was born. In decades past it was the only practical way out of town, for both people and freight. Central Wisconsin was littered with small towns that had once thrived but were now all-but-abandoned after the transition from rail to automobiles.

My seventh grade math teacher, Sam Ray, married to my first grade teacher, often told us stories about the Neillsville of his childhood in the 1920s and 30s, when having a car was a big deal, because it was possible to make the trek to a big city like Eau Claire in a half a day. But by now the roads were paved, cars were bigger and more reliable, and the same trip could be done in an hour.

Eau Claire was an important destination to us, and for most of my childhood it was the very definition of urban. My parents met there, at the Eau Claire State Teachers College, now the University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire Extension, so we had some familiarity with the place, but it was still considered a place to go on special occasions, no more than a few times a year. With a population of more than 60,000, it dwarfed any of the other places we could imagine visiting.

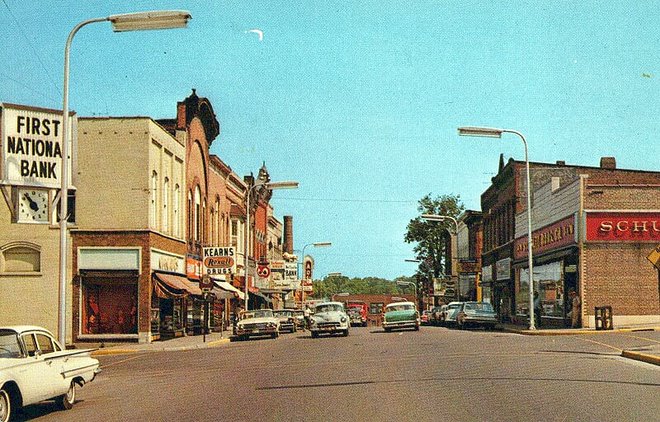

Neillsville, at 2,750 was itself the biggest city in Clark County (total population around 25,000), so we already thought of ourselves as a real city, unlike the smaller towns that dotted central Wisconsin: Greenwood, Granton, Hayward, Thorp, and many others. For shopping, you could buy most of what you needed in Neillsville. We had two grocery stores, a hardware store, car dealerships, furniture and department stores, a shoe store and more.

But still, for serious shopping, you would have to make the thirty-mile drive to Marshfield, which at 20,000 people made Neillsville seem small. Marshfield had traffic lights, fast food outlets (McDonalds! Kentucky Fried Chicken!) and even a tiny community college. Like Neillsville, Marshfield had a newspaper, but it published daily, not once per week.

Marshfield’s biggest employer, the Marshfield Clinic, was regarded as one of the better hospitals in the state, and possibly in the Midwest, attracting a small but important segment of well-educated doctors and medical practitioners, no doubt attracted by the small-town lifestyle in a natural setting.

That was our world: Neillsville, innumerable smaller nearby towns, the big city of Marshfield, and for very special occasions the huge metropolis of Eau Claire. The world beyond was, to us, mostly theoretical. There were the Really Big Cities, like Minneapolis and Chicago, and occasionally you would hear of somebody traveling there, perhaps to fly on an airplane (we didn’t know of any other way to travel by air). Our grandparents had met and married in Chicago, but left soon after that, and had nothing good to say about the place. Our uncle insisted that, if you ever find yourself needing to drive a route that takes you past Chicago, whatever you do, don’t go through the city.

That was fine advice, as far as I was concerned, though frankly a bit irrelevant. Why on earth would anyone need to visit a big city like Chicago when we had everything we needed right here?

1.2 Farmers

Neillsville since the 1960s and 70s has seen less change than many American places, if only because its rural location makes it too easy for the rest of the world to pass it by. The population when I was there, two thousand seven hundred and fifty, is about what it is today.

The 1980s were tough on rural agricultural towns like Neillsville, and many of the ways that Neillsville could be proud of itself went away. I’ve been back a few times since, but not enough to understand the subtler changes so it’s just my speculation that the general quality of the people has changed.

Dairy farming, and the agricultural life in general, was the defining pillar of the community. By the time I grew up, America had already shifted from an economy based on farmers, but that was all theoretical to us then. Today it’s hard to imagine, but my brother and I were considered “city boys” by the local standards. But even us city boys were very familiar with the smells and activity of a farm: the moist pungency of cows in a barn, the thick overhang of pollen in the hay fields, the long, hilly dirt roads out of town with red barns sprinkled lightly through forests and never-ending corn fields.

In middle school, out of emerging teenage spite, I chided one of my friends, a farmer’s son, that the world doesn’t really need farmers. “We’d find some other way to get food,” I insisted. I was imagining robotic planting and harvesting machines, maybe, or a world of genetic modifications and food grown in factory vats. Science, I thought would eventually make obsolete the old-fashioned, primitive ways of growing food. At the time, I meant this in a provocative, maybe mean-spirited and certainly immature way, but in the larger sense now I guess I was on to something.

Farmers today, even in Neillsville, are endangered. Yes, there are people who make a living from tilling the soil and raising cows, but more likely than not, they are employees of corporations, the big and efficient companies that now run agriculture like factories. Neillsville now boasts several of these multi-thousand acre enterprises, with a staff of specialists: a full-time expert for example whose only job is to determine which crops to plant in which field; a team of veterinarians to look after the herds; a foreman – maybe a group of them – looking after the dozens or hundreds of unskilled hands hired to do the menial and still labor-intensive jobs of putting up and repairing fences, driving tractors up and down fields, attaching and releasing milking equipment twice each day from row after row of cows. Those are not the farmers I remember.

My farmer friends were all families. You could say they were “family businesses” but the word “business” seems awkward somehow and not really applicable to people to whom this was a way of life. Our friends weren’t milking the cows in order to earn a living – though of course that was the net result. They were farmers because their parents were, and because that was what you had to do in order to eat. You can’t be a farmer if, to you, it’s a “job”; it’s a lifestyle. The farmers I remember got up in the morning to milk the cows, not out of any consciously expressed purpose (“it’s my job”) but because that’s just the way it is. Why do city-dwellers clean up their dishes after dinner? Why does a man in the suburbs mow his lawn? They do it because it’s something that has to be done. It would never occur to a farmer to think of his occupation as a “career”, in the sense that, oh I’ll just do this for a few years and then submit my resume to some company and switch to a different job. Farming, to a real farmer, is life itself.

On my, sadly, infrequent visits back to Neillsville since that time I find that few of my friends remained in farming. Farmers children nearly all went to college, it seems, and even those who majored in “agricultural studies”, ended up mostly in the cities, in other occupations. The few who remained behind, keeping up the family farms have migrated to organic farming, where the profit margins are higher, and where the benefits of direct attention to the farm is greater.

1.3 Tourism

Despite its central location geographically, Neillsville is about 30 miles from the nearest interstate highway, putting it almost three hours drive from the nearest big urban area of Minneapolis-St. Paul, and almost six hours from Chicago. That’s an impractical distance for day trips, so to attract visitors and their tourist money Neillsville has had to invest in various attractions, with varying levels of success.

There’s the natural beauty of course: rolling green hills in the summer, colorful leaves in the fall, white powder trails perfect for snow sports in the winter. When the Ice Age receded, it left a large moraine just outside of town, the top of which presented a beautiful view of the Wisconsin countryside. Sometime after I left in the 1980s, it was turned into a Vietnam Veterans memorial and today draws thousands of visitors a month.

On some measures, Neillsville could even beat our nearest big city of Marshfield: we had a radio station, WCCN (the call letters stand for “Clark County Neillsville”). The Clark County Jailhouse, now a museum, is listed in the US Register of Historical places.

But no other town has anything to compare to our biggest tourist attraction: the “world’s largest cheese”, housed in a special exhibit at the edge of town, a monument built for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. As if that weren’t enough to attract tourists, the occasion was further memorialized with a large outdoor statue of a cow in its honor. “Chatty Belle”, complete with a speaker and audio player will, upon deposit of a quarter, regale any visitor with a short missive about the wonders of our town.

Such was the tourism industry in Neillsville, and I guess it was reasonably successful since the “talking cow” and nearby Worlds Fair Pavilion are still there.