My Philosophy of Food

After years of careful studying too many books on health and human biology here’s what little I know about diet, exercise, wellness, and how to prevent and treat obesity and diabetes.

Everyone is different

This is the most important rule, which is why I put it at the top. In most advice books, it would be at the bottom as a parting reminder that we try hard but can’t guarantee this will work for everyone. But I start with this because I don’t believe there are hard fast rules, especially about something as complicated as diet and nutrition.

Since everyone is different, the most important advice is to be flexible, try new things, and most importantly, be aware of yourself and how your body changes over time as a result of the things you do.

Remember, too, that it’s easy to fool yourself into thinking that something is working or not working. We humans crave hope in any package we find it, so it is natural to seek answers when there are none. The only solution, not perfect unfortunately, is to think like a scientist: listen to your body, but rely as much as possible on data. Be guided, as much as possible, by things you can measure.

Now, given that everyone is different and always keeping that in mind, here are a few other hints, heuristics, rules of thumb, general ideas to consider, based on some long time observations, thinking, and reading that I’ve done on the subject.

Sweets are poison

Metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes are problems with the way the body processes sugar, so try as much as possible to eliminate them entirely. I say “try” because your goal is long-term sustainability, and if you veer too far from your comfort level, your resolve eventually breaks down. Don’t try to be super-human in the face of the impossible, but do push yourself as much as you can. That’s why I suggest thinking of sweet things as though they are a poison: you need to eat, and of course much food contains sugar, but to ween yourself as much as possible, start telling yourself that the taste of sweet things is terribly bad for you. Think of it like bad air days in Beijing: we all need to breathe, so when you’re outside and you have no choice, go ahead and take a breath; but stay indoors as much as you can.

Note that I say you should eliminate “sweets”, not just “sugar”. Although science has found a way to make chemicals that taste sweet-like without apparent effect on the measurements that usually seem to matter for sugars, I think it’s wise to be skeptical. Your taste buds evolved with the rest of your body, and whatever happens on your tongue and brain are not independent from what happens in your stomach, your blood vessels, your other organs like the pancreas. A cleverly-designed chemical might fool one or another of those organs but it would take great arrogance to think humans can design something that will fool everything all at once.

There is evidence, in fact, that because of the way artificial sweeteners prepare your body to take on new food, they are just as bad or worse than “real” sugars. The entire system that evolved to handle sugar properly senses an incoming onslaught, flips all the necessary switches to process them, and then – thud – nothing happens. When you do this once, perhaps the body responds with an “oh well, I guess it’s no big deal”, and there is no serious impact. But when you do this over and over, eventually the body will become inured to the sweet stimulus. If sometimes, or most times (if you ingest too much sugar substitute), the body gets the wrong signal, it may start to respond incorrectly to the real sugar too.

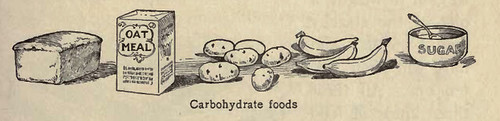

Carbohydrates are your enemy

Unlike sweets, which directly impact the system that breaks down in a diabetic person, carbohydrates work indirectly, because the body itself converts them into sugar.

Unlike sugar, you can’t – shouldn’t – eliminate all carbohydrates, but if you think of sugar as a poison that will kill you if you eat too much, think of carbohydrates like an enemy who should be avoided. When given a choice between carbohydrates and something else, choose the alternative, but don’t feel bad about indulging occasionally when it’s hard to avoid.

Pasta, rice, bread: these are your enemies. If you’re trying to lose weight, say no to them every time. But if an otherwise healthy item contains carbohydrates, go ahead and eat up.

Exercise responsibly

We need sugar for energy, which is the whole point of the digestive system, so another way to prevent the sugar poison from building up is to burn it off.

But too much, or the wrong type, of exercise can be counter-productive. When the body consumes energy, it needs fuel, which it gets at first from whatever is available in the bloodstream, and if necessary, from fat in cells that were stored away for exactly this purpose. But a temporary, extraordinary surge in energy requirements will also naturally add one more important change to your body: appetite. We are designed to want more food when we burn energy.

Think of exercise as an appetizer: a way for the body to prepare itself for a big onslaught of upcoming food. In fact, in a healthy person that’s exactly what happens when you eat after an intense period of exercise: the food replenishes, brings everything back to “normal”, and when everything is working correctly this cycle of “burn” and “restore” is exactly what the body expects.

The important thing to remember is that exercise, like everything else you do, changes the way the body behaves. If you increase one thing (exercise), you increase another (appetite). If heavy exercise is regular and predictable, the body will simply adjust by building an expectation that more food is coming. If you are too predictable, then skipping the exercise won’t let you skip the food, and you’ll find yourself unusually hungry. If the whole point of exercise is to burn off energy in order to burn down some of the stores of fat, then irregular exercise will be counter-productive.

Exercise and diet. Don’t do just one or the other.

Think about food, not ingredients

The body processes food in an incredibly complex way, and although science has made great progress by breaking food into its individual components, the research is still in its infancy. Very little is really known about the relationship between the components of what we eat: the interaction between fiber and carbohydrates, say, or sodium and sugar when consumed together. There are also many additional components of food that remain unstudied, presumed today to be unimportant, but just waiting new science to burst on the scene as a new nutritional breakthrough.

A dill pickle, for example, shows up in nearly every diet book as an irrelevant food: no calories or nutrition to speak of. But as a product of fermentation, it can be a major source of probiotics that, recently, food scientists are just beginning to study.

The solution is to think of food as food, not as a pile of ingredients. You are safer when you choose to eat things that are as close as possible to their natural state, or at least to the state they have been eaten for hundreds or thousands of years.

Pills and extractions are rarely a substitute for consuming food intact, with all the glorious interactions among its internal components.

It follows that you should, wherever practical, eat only real food – the complex products of nature, as consumed by ancestors since pre-history. New products, even when promoted as “healthy” or “natural” are rarely able to meet the standards of subtle interconnected complexity that you get from nature. Avoid artificial butter and sweeteners, and be skeptical about any product using a new process for preservation or nutrition.

Practical Suggestions

Remember Rule # 1: everyone is different. You can’t know which techniques work for you unless you try, so here are a few ideas:

- Measure: if you want to lose weight, measure your weight regularly. Better yet, tell others, and make yourself accountable. This will often work even if you have no particular goal, because the simple act of being mindful will affect the rest of your actions.

- Fast: by regularly throwing your body off kilter through skipping food, you become more efficient at using what you have. And by allowing yourself to feel, and overcome, hunger, you build up resistance to eating simply because “it’s meal time”.

- Manipulate the set point, through regular large doses of fat. Seth Roberts suggests 2-3 tablespoons of olive oil consumed in mid-morning as a way to satisfy the body’s need for food and allay hunger for the rest of the day.

- Variety: As much as possible, try different foods or exercises. Avoid eating the same breakfast more than once per week. Try different forms of exercise, at different times.

These are my rules. They work for me.